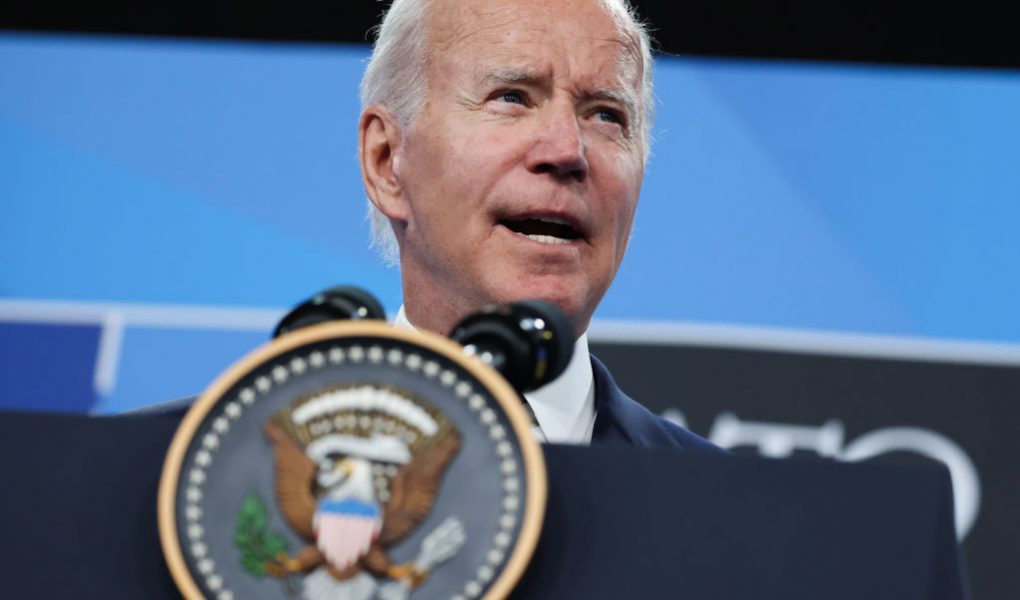

During his trip to Israel and Saudi Arabia this week, U.S. President Joe Biden will seek to reassure long-time partners that the United States remains committed to the region’s stability and security. But the elephant in the room is the fact that almost no one will believe him.

The cumulative damage done during more than a decade of presidents from both parties pivoting out of the Middle East has been too great. Simply showing up won’t be nearly enough to stop the accelerating rot that has taken root in the U.S.-led security order that has helped underwrite the region’s stability for most of the past half century. If Biden truly aspires to break the dynamic of eroding U.S. credibility and deterrence, he’ll need to go well beyond photo-ops and the happy talk of his recent Washington Post op-ed and make clear that his visit marks the start of a more fundamental shift in U.S. strategy from retrenchment to recommitment.

It won’t be easy. The trajectory of U.S. disengagement has, in many respects, reached its apotheosis during Biden’s first 17 months in office. The catastrophic retreat from Afghanistan, leaving thousands of the United States’ allies stranded behind enemy lines, was perhaps exhibit A, especially for vulnerable Arab regimes that have historically bet much of their security on the power, reliability, and competence of their U.S. superpower patron.

But the bill of indictment is much longer. It includes Biden’s pledge to turn Saudi Arabia, Washington’s oldest and most influential Arab partner, into a “pariah” over Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s responsibility for the horrifying murder of U.S.-based journalist Jamal Khashoggi; suspending arms sales to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates in the middle of their war against Iranian-backed Houthi rebels in Yemen; withdrawing U.S. air defense assets from the Persian Gulf at precisely the moment Houthi drone and missile attacks on Saudi population centers and critical infrastructure were at their height; and refusing to respond, or inadequately responding, not only to dozens of Iranian-backed attacks on U.S. troops and diplomats but to unprecedented drone and missile assaults against longtime allies like the United Arab Emirates.

Making it all infinitely worse has been the administration’s open-ended effort to lure Iran back into the 2015 nuclear deal, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action. Most of Washington’s most powerful regional friends—including the Saudis, Emiratis, and Israelis—oppose the agreement as a sure-fire recipe for empowering Iran and supercharging its program of regional aggression.

It’s a lot to overcome. Just how bad things have gotten was shockingly manifested in reports this year saying that not only had Saudi Arabia’s de facto leader, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, rejected Biden’s pleas to increase oil production to help curb skyrocketing U.S. inflation in the face of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, but he’d also balked at even taking Biden’s call to discuss the issue. Less headline-grabbing, but no less worrying, have been a steady stream of Saudi and Emirati hedging behaviors toward Russia and China—from military cooperation agreements, weapons purchases, and ballistic missile-production deals to constructing secret naval bases, acquiring Huawei 5G technology, and threatening to price oil sales to China in yuan.

Finding himself in a death match with Russia over global energy markets only to turn around and discover that Saudi Arabia, the world’s most important oil producer and a strategic partner of almost 80 years, was no longer reliably in the United States’ corner, was no doubt a rude awakening for Biden. His efforts to downgrade and demean the relationship with Riyadh backfired and actively harmed U.S. interests during one of the worst crises for U.S. foreign policy since World War II. That helps explain Biden’s difficult decision to eat crow and travel to the kingdom this Friday in an effort to make amends—despite the howls of protest from many in his own party.

But while it might help get Biden’s phone calls answered in the future, the visit is unlikely to be enough on its own to address the real long-term threat to U.S. power and influence in the Middle East: the slow bleed of U.S. credibility as a reliable security benefactor, which has heightened instability in what remains the most important region for the world’s energy supply—and thereby, for the global economy. Simply adjusting the balance of Biden’s current policies at the margins—a little less appeasement of Iran, a little less antagonism toward the Saudis—is unlikely to be sufficient to staunch deep-seated concerns about Washington’s strategic commitment to the region. The perception that the United States is irreversibly in the process of removing itself from its historical role at the center of the Middle East’s security equation is now too far down the tracks. Derailing it at this late date will probably require more drastic steps.

Like what? One not entirely obvious place to look for inspiration would be the former U.S. presidency of Jimmy Carter. By late 1979, following the seizure of American hostages in Iran and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, U.S. credibility in the Middle East was hemorrhaging. Carter responded in his January 1980 State of the Union address by announcing what became known as the Carter Doctrine, a major statement of policy that committed the United States to use any means necessary, including military force, to repel an outside power from gaining control of the Persian Gulf region.

Today, a Biden doctrine would explicitly and unequivocally recommit the United States to use all elements of national power, including force, to defend its vital interests in the Middle East—blocking Iran’s bid for a nuclear weapons capability and regional hegemony as well as constraining malign Russian and Chinese penetration of the region. A new doctrine would emphasize the priority of strongly supporting the United States’ most powerful partners—Israel, Saudi Arabia, and other countries in the Arab world—to forge a new U.S.-led alliance system to jointly counter shared threats. As part of the bargain, Biden should insist that the most troubling cooperation with China and Russia by the United States’ regional partners needs to cease; this kind of hedging with other great powers should no longer be necessary if Washington convincingly recommits to defending the region’s security. In an era of renewed great-power rivalry, including the outbreak of a major war, neutrality from U.S. allies on critical threats to the international order should not be acceptable. It would consciously and unmistakably seek to repudiate the last decade’s dominant narrative of U.S. withdrawal from one of the world’s most critical regions. It would forthrightly declare that the days of any U.S. pivot away from the Middle East—ill-considered, unwise, and dangerous—are officially over.

But don’t hold your breath. There’s little reason to believe that Biden is up to the task. His weekend op-ed included a laundry list of mostly dubious claims about how much better his policies had already made things in the region. As for Carter, Biden’s political advisors no doubt would recoil at any suggestion that might draw comparisons with the country’s last Democratic president to be soundly rejected in a bid for reelection.

Still, the Carter Doctrine became one of the most consequential foreign-policy initiatives of the past 50 years and remained the cornerstone of U.S. strategy in the Middle East long after Carter had departed the White House. As Biden girds the United States for a new cold war against a rising China and revanchist Russia, and as the importance grows of making sure that the pivotal states of the oil-rich Middle East remain firmly and reliably in the U.S. camp, he could do a whole lot worse than emulating the 39th president. A revival of the Carter Doctrine would help get the United States back on track in the coming generational struggle against its most dangerous adversaries.

John Hannah, a former national-security advisor to Vice President Dick Cheney, is the Randi and Charles Wax Senior Fellow at the Jewish Institute for National Security of America (JINSA).

Originally published in Foreign Policy.