In May, Russian President Vladimir Putin greeted Alexei Likhachev, the director general and CEO of Russia’s state-owned nuclear enterprise Rosatom. Putin took the opportunity to congratulate Likhachev, whom Putin had personally appointed to the job nearly six years ago, on accomplishing “a great deal of work.”

Rosatom’s commercial exploits have indeed been significant. In the company’s relatively short 15-year history, Rosatom had grown to employ more than 275,000 people and brought in $16 billion of revenue in 2020. The corporation boasts on its website of having the largest foreign portfolio of any nuclear company, with 35 nuclear power units under development in 12 different countries.

But Rosatom’s biggest coup has been its hostile takeover of Europe’s largest nuclear power plant. In the early days of March, invading Russian forces took control of the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Station, located in southeastern Ukraine. A week later, Russian officials gathered the plant’s management and told them the plant now belonged to Rosatom. Hundreds of Russian soldiers now corral Ukrainian nuclear scientists, while dozens of Rosatom officials have spent the past five months attempting to transform the station from powering the Ukrainian grid to Russian lines instead. In the first month of the war, Rosatom also took control of the Chernobyl nuclear site, where they looted and destroyed $135 million worth of computers, radiation dosimeters, and safety equipment from the fragile area.

As Russian forces have faced escalating attacks from Western artillery systems, they have been using the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant as cover to launch rocket attacks against Ukrainian forces. On Aug. 8, the Russian military commander in charge of forces at Zaporizhzhia announced that they had set charges to the nuclear power facilities and declared “the plant will either be Russia’s or no one’s.” The unfolding disaster prompted the director general of the IAEA, Rafael Grossi, to remark on Aug. 3 that “every principle of nuclear safety has been violated” and that the situation is “out of control.” Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky has called for the international community to impose sanctions on Rosatom.

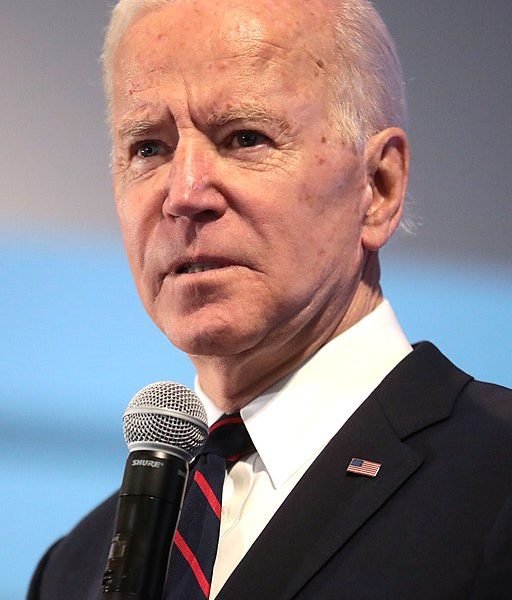

However, instead of sanctioning Rosatom, the Biden administration appears to be rolling out the red carpet.

The top U.S. nuclear official is set to share the stage with Rosatom’s No. 2 executive at a D.C. conference on Oct. 26. Rosatom’s first deputy director general, Kirill Borisovich Komarov, is scheduled to speak in Washington, D.C.’s main convention center alongside the U.S. Department of Energy’s Assistant Secretary for Nuclear Energy Kathryn Huff in an IAEA session focused on “the establishment of an enabling environment for the safe, secure, and sustainable use of nuclear energy.”

It remains unclear why Secretary of State Antony Blinken thought it would be prudent to issue a visa for a Rosatom official to testify to an international audience on best practices of the “safe” and “secure” use of nuclear energy when Rosatom is guilty of participating in one of the greatest breaches of nuclear safety since the Chernobyl disaster.

Still, Blinken’s support for Rosatom is not limited to issuing visas. I obtained unclassified State Department documents showing that Blinken issued a series of sanctions waivers on Aug. 3 permitting U.S. and international companies to engage in cooperation with several parts of Iran’s nuclear program. The predominant benefactor of these sanctions waivers is Rosatom and four of its major subsidiaries, which provide services to various parts of Iran’s nuclear industry. The waivers would permit Rosatom to provide operations, training, and services to the Bushehr Nuclear Power Plant.

A decade ago, Rosatom built the first reactor at Iran’s Bushehr nuclear site. But according to official Russian and Iranian documents I obtained and translated, Rosatom has also engaged in a $10 billion contract to construct two additional nuclear reactors at Bushehr that would generate a combined 2,100 megawatts. These reactors are scheduled to be put online in 2024 and 2026. The contract also provided for the possibility of Rosatom constructing an additional six or more nuclear reactors at Bushehr and other sites in Iran in the future. Russian work at Bushehr had stalled in recent years because of Iran’s inability to pay its bills to Rosatom. The Atomic Energy Organization of Iran owed Rosatom $500 million for previous work, and Russia’s ambassador to Iran complained last August that Iran couldn’t pay up because U.S. sanctions on Iran had blocked the regime’s funds in Japanese and South Korean banks.

But in late May, Russia’s deputy prime minister announced that Iran had paid part of its debt to Russia in “late 2021 and early 2022.” The regime was likely able to make the payment due to lax U.S. sanctions enforcement on Iran, which caused the regime’s foreign currency exchange reserves to skyrocket from $4 billion at the end of the Trump administration to over $41 billion by the end of this year.

Iran was also incentivized to make the payments to Russia when the Biden administration issued an earlier set of these nuclear sanctions waivers for cooperation with Iran’s nuclear program just three weeks before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. State Department officials conceded at the time that these waivers meant the United States would “not sanction Russian participation” in Iranian nuclear projects. A bill in the U.S. Senate sponsored by 13 Republican Senators would rescind these controversial waivers. The February waivers were issued before Russia’s invasion and Rosatom’s involvement in the takeover of Ukraine’s nuclear power plant. But this latest renewal, which provides full sanctions immunity to the Russian companies’ work in Iran over the next six months, was made with full knowledge of Rosatom’s involvement in the takeover of Zaporizhzhia and their destruction at Chernobyl.

In the past several months, Iran has also aided Russia’s war against Ukraine by sending attack drones to Russia. The Biden administration has yet to sanction any Iranian individuals or entities for providing these weapons to Russia.

Rosatom is a crown technical and financial jewel of the Russian economy and provides a vital lifeline to Putin’s war machine. The U.S. should heed Zelensky’s exhortations and sanction Rosatom, its subsidiaries, and its senior leadership. This will be a difficult task, as swaths of the U.S. nuclear industry still rely on Russian nuclear fuel. But at a minimum, the Biden administration must stop rolling out the red carpet for Rosatom and work to disrupt its lucrative nuclear contracts with Iran.

Gabriel Noronha is a fellow at the Jewish Institute for National Security of America and previously served as special adviser for Iran in the U.S. State Department from 2019-2020. He also worked in the U.S. Senate from 2015-2019, including on the Senate Armed Services Committee for Chairmen John McCain and Jim Inhofe.

Originally published in Washington Examiner.