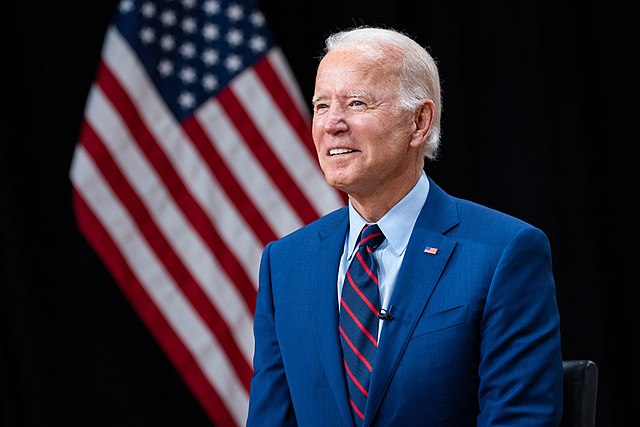

As President Joe Biden toured the Middle East, one of his first stops was to see an Israeli air defense system known as Iron Beam.

On February 1, 2022, then-Israeli Prime Minister Naftali Bennett announced Israel would create a “laser wall” within a year that would protect the country against rockets, missiles, and drones. This claim appears overly ambitious but highlights the rapid progress of directed energy technology. Israeli state-owned Rafael is producing the ground-based Iron Beam with a range of 4.3 miles, while the Israeli firm Elbit is developing an airborne laser that attaches to aircraft.

Israel has threats aplenty to contend with in the region, but they’re not the only ones. Facing a rise of Iranian-backed aggression throughout the Middle East, the US, too, should engage in joint development of directed energy defense systems that could provide more efficient and improved security for all US allies and partners – including Gulf nations.

Biden’s trip coincided with newly revealed efforts by Israel to create an unprecedented, interlinked, regional air defense system. The first steps to building this architecture are forming a common air threat picture, R&D and technology sharing. In this, Biden should work to facilitate bringing Israeli defense technology to Gulf states, perhaps even as far as laser defenses, as suggested in one recent report.

Directed energy systems, like Iron Beam, could drastically decrease the costs of intercepting projectiles. A single-use Israeli Tamir interceptor for an Iron Dome battery costs between $40,000 to $100,000, while militants frequently fire munitions costing only a few hundred dollars — a cost equation that encourages aggression. Iron Beam, although expensive up-front, only requires electricity to function and could reduce the cost of each interception to roughly $2.

Once operational, laser air defenses would have immense benefits for American personnel and regional partners in the Middle East, who routinely face Iranian-linked mortars, rockets, missiles, and drones. Iran’s regional proxies fired roughly 740 projectiles at US personnel and Arab nations in 2021, compared to approximately 500 in 2020, according to data from the Jewish Institute for National Security of America. These groups are on pace to set another record this year, having already launched over 400 projectiles in the past six months.

To defend against this threat, the US has sent air defenses to Iraq, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) that have intercepted Iranian-linked projectiles. But these deployments have been too small, slow, and often temporary.

JINSA’s data also highlights the growing threat from Iranian unmanned aircraft systems (UAS), commonly called drones. Between 2018 to 2020, drones were less than 40% of the munitions Iran-backed groups fired at the US and its partners in Iraq, Syria and Saudi Arabia but have been half of the projectiles since 2021. In February, US aircraft shot down two Iranian-linked drones in Iraq headed toward Israel, which was reportedly part of an evolving air defense partnership involving Israel and Arab nations.

Directed energy could be particularly useful as counter-unmanned aircraft systems (C-UAS) because of their ability to neutralize small and swarming objects that current platforms miss. Israel’s F-16 aircraft and Iron Dome have previously intercepted drones, and the United States has deployed several C-UAS options, but no single system can efficiently track or intercept the wide range of evolving threats. The Pentagon should explore collaboration with Israel on this important emerging technology as it has done in the past with other air and missile defense capabilities.

The development of directed energy would also make regional partners less susceptible to delays or hesitancy in Washington to resupply air defense interceptors. America’s regional partners have been concerned about its commitment to the Middle East. Despite Biden’s pledge immediately after the May 2021 conflict between Israel and Hamas to rearm Israel with Tamir interceptors for the Iron Dome, Congress struggled to pass the necessary appropriations for ten months. Such a delay in a major conflict could be disastrous.

Yet, lasers are not a panacea. While they operate at the speed of light, can be recharged for deeper cost-effective magazines, provide near instantaneous tracking and engagement, and usually operate at invisible wavelengths for low probability of detection, the current technologies have several weaknesses. Many systems do not currently work well in poor atmospheric conditions and are relatively limited in their power and range. Therefore, directed energy is not a replacement of other kinetic defenses but a means of providing an improved, wider range of defensive capabilities against the multitude of threats at a lower cost.

To fully leverage this emerging technology, the United States and its partners should enhance collaboration on joint air defense R&D, including directed energy. If testing for Iron Beam or other Israeli technologies proves successful, Congress should explore coproducing these systems, as it has done with Iron Dome.

Retired US Air Force Lt Gen Henry A. Obering III served as the director of the Missile Defense Agency and is a member of the Jewish Institute for National Security of America’s (JINSA) US-Israel Security and Iran Policy Projects. He provides executive counsel to Booz Allen for their ongoing directed energy efforts in the US but has no connection to the Iron Beam effort in his industry capacity. Ari Cicurel is a senior policy analyst at JINSA.

Originally published in Breaking Defense.